What does the upcoming Iraqi election mean for Assyrians in 2018?

Iraq 3.0 is about to get going this month. ISIS has been territorially defeated and pushed into adopting insurgent tactics once again. Minoritized groups such as the indigenous Assyrians and Yazidis are trying to piece their lives back together in their ancestral homeland of the Nineveh Plain — an area rendered fertile for onslaught and occupation after a decade long campaign of destabilization waged by the Kurdistan Regional Government as a prelude to ISIS.

Among the ruins, hope emerges for these brutalized and battered people. Christian Assyrians were among the biggest losers in The New Iraq, having put down their weapons after the overthrow of Saddam in compliance with coalition policy, thereby rendering themselves defenseless amid the ensuing sectarian strife and violence. Meanwhile, disparate groups of Arabs and Kurds continued to reinforce their arsenals in a bitter struggle for land and power that seems to persist indefinitely.

Iraq’s democratic experiment has thus far only yielded unprecedented levels of corruption and failure, but there is a new dawn in Iraq brought into full view after the defeat of ISIS. A small modicum of positive energy has been rekindled among much of the population, and a renewed belief in the Iraqi armed forces has reignited some optimism about the future of a Federal Iraq.

It is no secret that the Federal Government has repeatedly failed the most vulnerable groups in the country — both legislatively and materially — as it grappled with a new found freedom from dictatorship. When Iraqis lose, Assyrians lose more — such is the nature of the relationship between minoritized groups and a state historically unable to enforce law and security free of sectarianism and leveraged deal-making. In this endeavour, Assyrians cannot call on any powerful sponsor — a prerequisite for survival, nevermind prosperity.

As usual, Assyrians enter these elections allotted a minority quota of 5 seats in the Iraqi Parliament. Each list — a mechanism which enables Iraq’s numerous political parties to run together and then share power given success — must comprise of 10 candidates. This compliments the system of proportional representation Iraq utilises which almost always never sees one single party garner a majority in parliament, almost necessitating the need for negotiation and compromise between parties after the election has been concluded. The most recent figures I have seen confirm a total of 6,904 candidates within 143 political parties (204 total, with rest being “independently” represented) over 32 lists will contest the upcoming elections.

As of writing, there are 67 Assyrian candidates spread across 7 different lists running for 5 quota seats in parliament. This means that 7/32 lists, and 67/6,904 candidates are Assyrians contesting 5 quota seats reserved out of a parliament of 329 seats. To give you another angle: 22% of the officially registered lists are contesting 1.5% of the total seats available. If that ratio seems off and embarrassing, that’s because it is. But we have to understand these numbers. Never have so many people contested for so little.

Here is a brief who’s who and what they represent and thoughts on the quota system:

List 113 — Chaldean Syriac Assyrian Popular Council (or Majlis Shabi)

Majlis is a political party founded and funded by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) in 2007 through its willing accomplice and former Minister of Finance, Sargis Aghajan — an ethnic Assyrian. Its purpose was to both muffle any independent Assyrian political voice whilst buying loyalty from Assyrians to push KDP policies, namely the annexation of Assyrian territories to the KRG. Sargis Aghajan was the face of this party until his disappearance from all public life after the break of Wikileaks, and his revelations therein.

The Zaito clan — who own and administer Babylon Media — are staunch supporters of this list. Salwan Zaito recently declared that Aghajan did “the work of Jesus” at a political rally, inspiring the wrath of Chaldean Patriarch Louis Sako in a politically charged rebuttal. Majlis also endorse the Nineveh Plains Guards — a force formed in 2007 of unknown size and capability—who fall squarely under peshmerga command. The KDP ventriloquise Majlis into asserting this proxy force as the rightful defenders of the Nineveh Plain, despite having no operational value outside of a few flashy propaganda videos. Many leadership figures in the Churches serving the Assyrian people also support this force, in line with KDP policy.

Wahida Hermiz, a Majlis MP in the Kurdistan Regional Government, regularly appears on Kurdish media outlets owned by the Barzani family declaring her support for an independent Kurdistan and condemning any other military force in the Nineveh Plain other than peshmerga. These activities are in line with the party’s international efforts: Loay Mikhail has been a paid lobbyist for Majlis (and by extension the KDP) in Washington D.C. for years. His job, as seen here, is to push for the annexation of the Nineveh Plain to the Kurdistan Region through direct lobbying and the undertaking of collaborative political activities, none more pronounced than lauding the coalition of traitors present at the Brussels Conference last year. He also serves as a senior adviser for the “Safe Haven Project” overseen by the group In Defence of Christians alongside Western opportunists like Stephen Hollingshead — who also advocates for Majlis policies (annexation of the Nineveh Plain, support for the peshmerga-controlled Nineveh Plains Guards).

Most recently, the KDP have been mobilising people, including Kurds, to vote for Majlis candidates, specifically Rehan Hana Ayoub in Kirkuk — whose quota seat is currently occupied by Imad Youkhana from the Assyrian Democratic Movement (ADM). This has brought about condemnation by the Sons of Mesopotamia political party (Abnaa Nahrain) who are also contesting this seat. Majlis currently holds two seats in Baghdad’s parliament.

List 115 — United Beth Nahrain

This list is primarily composed of members of the Beth Nahrain Democratic Party and Union— two more Kurdistani parties, albeit two which hold no seats in parliament. Curiously, Joseph Sliwa — an ethnic Assyrian member of the Iraqi Communist Party — is the only person on the list who currently holds a seat in Baghdad’s parliament. The head of the BNDP, Romyo Hakkari, regularly appears on Kurdistan 24 and Rudaw — media channels operated and funded by the KDP — pushing KDP policies (such as the failed referendum) and propagandizing for the annexation of the Nineveh Plain to the Kurdistan Region (a referendum on annexation is a KDP policy — they would assure a favourable outcome).

The BNDP’s military extension, the Nineveh Plain Forces (NPF) were launched as part of the KDP’s response to the Nineveh Plain Protection Units (NPU), and comprised of a 50-strong unit of men who fell completely under Peshmerga command during the ISIS offensive. KDP media were keen to direct journalists and observers towards this group and away from the NPU. Since the annihilation of ISIS as a territorial force and the thrust northwards in the Nineveh Plain from the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF), the NPF has since disappeared, serving as they did no operational function — unlike the NPU who participated directly in the liberation of Assyrian towns.

List 131 — Syriac Assembly Movement

This list, three members short of a full ten, has Salwan Momika as its key figure in the background. Momika and his affiliates are another group of Kurdistanis who are, much like the BNDP and Majlis, not secretive about their KDP proxy status. The newly installed mayor of Bakhdida, the largest Assyrian town in the Nineveh Plain, is an affiliate of the BNDP and Dawronoye movement — voted in as he was by the corrupt and KDP-dominated Nineveh Provincial Council by a ratio of 12–1. This “movement” officially holds one seat on this council too.

There is little else to note about their potential to grasp power save for the fact that the “Syriac” vote has not been primarily determined by sect affiliation in the past, and is thus almost entirely divided between existing parties. A brief foray into military affairs by Momika only yielded a Facebook page, a few guys holding the red Aramean flag, and a few photo opportunities with the now defunct NPF — two branches of the same dawronoye tree.

This list holds no seats in Baghdad’s parliament.

List 139 — Chaldean Alliance List

Louis Sako, the Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church, has decided to formally weigh in on Iraqi political affairs by helping form and endorse a list of candidates along sectarian lines. Deliberately breaking with reality and the truth of peoples, Louis Sako is pushing an agenda which declares Chaldeans are a separate ethnic group from Assyrians, and is hoping to reap the benefits of doing so via a political platform. He even goes so far as rejecting the tri-name, Assyrian-Chaldean-Syriac, fashioned as it was to simultaneously “unite” and reward the sectarianism espoused by the main Churches serving the Assyrian people.

What has since emerged is a flurry of activity on social media pages as well as on the ground (and even diaspora student pages). The Chaldean Church is actively pushing its parishioners to vote for Chaldean Alliance candidates, even urging parishioners to do so during Church services. There are also stories of blackmail and withholding of services perpetrated by the clergy within diaspora communities. However, the rewards of instituting such despicable behaviour remain to be seen: if these threats, the blackmail, coercion and priestly authority translate into votes, the Assyrian community as a whole will suffer for it at a time they can ill afford to.

Regarding policy, there is nothing distinctive about this list other than pushing a sectarian identity as a platform. The members of this list are politically Kurdistani in that they and those who endorse them fully support KDP policies much like Majlis — the pool of voters Sako is targeting. In 2016, Sako personally went as far as discouraging support to the NPU during the height of the ISIS offensive, calling for Assyrians who want to contribute to security to either join the peshmerga or Iraqi Army proper. His subordinates, such as second in command Archbishop of Arbil Bashar Warda, echo this sentiment and push for some configuration of peshmerga and the Nineveh Plains Guards attached to Majlis to have jurisdiction in the political and military battleground of the Nineveh Plain.

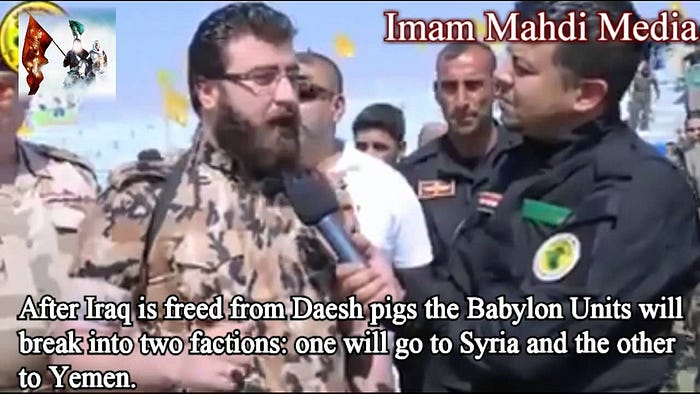

List 166 — Babylon Movement

Amongst the Assyrian community, this list is largely an unknown given that it is a political project by prominent Arabs affiliated to the Badr faction of the Popular Mobilisation Units (PMUs). Riyan Kildani is the face of the Babylon Brigades, an overwhelmingly Arab militia with a Christian face serving as its political arm. The initial thrust of this project was projecting a diverse PMU, but has since evolved into an opportunistic land grab of territories in Nineveh by Arabs who recognise the economic and geopolitical significance of having influence in these areas. The Assyrian community simply have no ties to it.

A curious recent addition to this list is Faiez Abdmikha (Jahwarah), the Assyrian mayor of Alqosh who was deposed by the KDP-dominated Nineveh Provincial Council. Abdmikha notably had an existing relationship with Riyan Kildani — both being natives of Alqosh. The prospects and potential success of this list are unclear, but it is incredibly unlikely they will garner any support among the Assyrian community. Will they be able to attract the votes of others through bribes and corruption? Quite possibly. If the prominent Arabs orchestrating this from behind the scenes were serious about rehabilitating the Assyrian presence in Nineveh, they would not be standing up a rival force to the NPU, much less a rival political player. Here, they are behaving in an identical manner to the KDP. The fact that this list has been put together proves that another problem is being deliberately created for the already besieged Assyrian community.

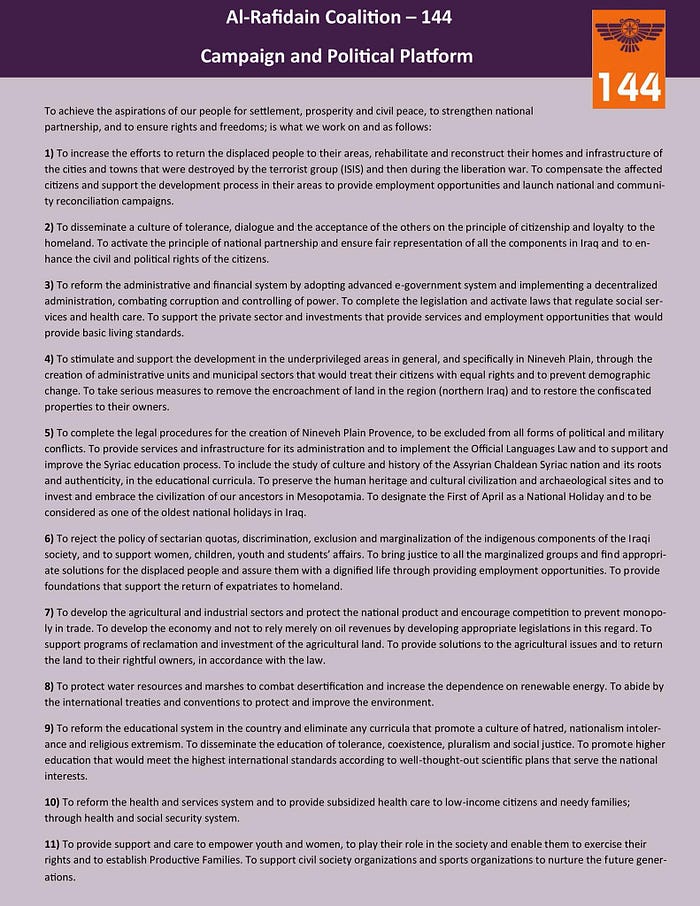

List 144 — Rafidain List (Assyrian Democratic Movement — ADM)

This list is mostly composed of Assyrian Democratic Movement (ADM — or Zowaa) candidates, bar Emanual Khoshaba, the head of the Assyrian Patriotic Party, and one of his associates. Khoshaba was the political leader of the Dwekh Nawsha militia — a unit of 10–20 men of varying origins whose primary output as a force was social media activity. This anomaly aside, proving as he does only to diversify the list of ADM candidates, the list is headed by apex politician Yonadam Kanna, the long-standing leader of the ADM, who won the last internal leadership contest with no rival and every single vote (which I critique in the second half of this piece).

This omniscience and omnipresence has yielded a lot of cynicism and resentment among many Assyrians. Some individuals unsuccessfully attempted to dislodge him at through the yearsand have since left to form their own political party — Abnaa Nahrain — who are contesting the elections as the only other Assyrian party not under the spell of Kurdish or Arab groups and agendas. At this time however, it is best to focus on policies and not individuals. The ADM are the political party which sponsors the NPU — the first legitimate force of Assyrians recognised by both Iraq and coalition forces. They have also consistently worked on a Nineveh Plain Province solution, which was voted on and passed in principle in 2014 in parliament. In Iraq at present, the ADM serve as the NPU’s political channel — crucial in order for the NPU to survive operationally in the ongoing administrative chaos of Iraq’s northern territories.

The ADM occupy a significant place in the imagination and memory of many Assyrians, being as they are the first Assyrians to organise and rebel against the Ba’athist regime in 1979. In this fight, they offered martyrs and many families are haunted by these losses to this day. After 2003, they have struggled to assert themselves in the corrupt machinery of the Iraqi political system, dominated as it was (and still is) by a new political order defined by greed. Assyrian numbers continue to dwindle in the face of Islamic extremism and Kurdish nationalism and gangsterism. Swathes of land have been stolen and homes lie in rubble or have their deeds simply rewritten — the question for Assyrians is always how much can our political representatives be blamed for our woes? Here is their election platform:

In this, inspecting policy is always best. However, most of what is written on paper inside Iraq in terms of defined actions must often be kept secret to prevent groups like the KDP from dedicating its considerable resources towards thwarting them. The most important accomplishment the ADM have played a key role in is the formation of the NPU. This success cannot be underestimated or overlooked in relation to our present and future in Iraq. It is action — not simply words and promises offered by the other parties. It is a force salaried by the Federal Government and recognized and trained in part by coalition forces. No other group competing for support from the Assyrian people has come close to demonstrating the capacity to build power by asserting our agency amid a sea of hostile actors. No other group vying for votes publicly supports the NPU either.

Yacoub Yakoo, an Assyrian ADM MP in the KRG asks the question in a pointed reference to KDP proxies, “why is Zowaa (ADM) a target for all of the non-Assyrian parties? Why have these parties spent millions of dollars creating problems for us, dividing us, and trying to drive us out of parliament?” He claims it is because the ADM are the ones who adopt and follow through on pro-Assyrian policies. And he is right. They were the ones to push for a Nineveh Plain Province in parliament, and they sponsor the NPU. The ADM currently holds two seats in the Iraqi Parliament — Baghdad and Kirkuk.

List 154 — Sons of Mesopotamia (Abnaa Nahrain — AN)

AN is a political party whose leadership is composed almost entirely of ex-ADM members and dissidents. In this, they are not a creation of the KDP, nor do they serve any other agenda. They are entirely a protest party and organise themselves accordingly, both to good and bad effect. The good means Kanna’s pragmatism is sometimes abandoned in favour of more overt expressions of disapproval or approval — towards Assyrian interests. The bad sees them withhold support for the NPU since it is sponsored by a rival political party (equalising them as they did to the other fake militias owned by the KDP), regardless of the benefit Assyrians feel in real terms by having them secure our towns as we try and rebuild them — against Assyrian interests.

One AN candidate recently referred to the NPU as the “NP-Gnu” (steal, theft), only to claim that is only what certain individuals have called the group in the Assyrian town of Bakdida. Relaying the words of what some people allegedly say in Iraq is in itself an act of bias and calculation. A lot of people say a lot of things. What is reported is always selective — by journalists, politicians and ordinary citizens. The least we owe ourselves and each other is taking responsibility and ownership for what we select — and backing it up with evidence if challenged on it. Once quizzed however, no evidence was presented to support this. Odd behaviour by a party official: if one cannot identify any evidence of a serious allegation that has come to one’s attention, one simply should not keep it alive by repeating it. Thus, this reference was nothing but a cheap slur.

The party consists of academics, lawyers and even poets. It is the party self-identifying intellectuals among the Assyrian community will naturally gravitate towards — especially those who are obsessed and resentful of Kanna’s hold over the ADM, and are all too ready to believe anything negative about him and the party. Here, AN seek to be a home for anti-Kanna sentiment to flourish. The problem with this self-imposed characterisation is that they deliberately render themselves a short-term project which runs parallel to Kanna’s political career. It has even led AN to push several lies about the ADM during the election campaign: most notably claims of how the ADM do not ask for anything, and have not achieved anything, and that they are an inert and idle political force. These claims are plainly untrue: the ADM has repeatedly worked on pro-Assyrian policies — some have succeeded and came to fruition like the NPU and the passing of the Nineveh Plain province in 2014, and some have been foiled by the KDP, most notably the scuppering of the province plan in 2007, and when a force of Assyrians was created in Nineveh but ultimately dismantled by the KDP in 2008.

The resentment is so great that it wrecked plans for AN and the ADM to run on a joint list to increase their chances of success. The deal fell through after terms regarding the composition of the single list were not agreed. According to contradictory reports: the ADM claimed AN wanted Kanna off of the list altogether, whilst AN claimed they merely said he should not be head of the list. The failure of these negotiations is ultimately an opportunity missed at the most crucial of times. Both parties failed the Assyrian community with this petty bickering to an extent, yet in the context of these elections and what is at stake (namely, the NPU), it was AN’s protesting and subsequent lying which is ultimately far more to blame.

AN currently hold no seats in Baghdad’s Parliament.

Does the quota system work for Assyrians?

The quota system is supposed to reserve minorities a seat at the table to relay their demands, but we must examine what these seat(s) have yielded in terms of benefits in order to manage our expectations of them. It seems that our situation is always getting worse, and this reached its peak with the onslaught of ISIS. The seats occupied by the ADM were useful in legitimising an Assyrian militia in the theatre of war to reclaim territory. This political face enabled the NPU to take its place among all other groups in Iraq, demonstrating that Assyrians are equal to all other constituent groups and capable of fighting for our own place in the country. Without the ADM’s offices, logistical nuance, political relationships and supporter base, the NPU would exist as it does today. Without the NPU, Assyrians would only be able to call proxy militias with no operational value managed by Kurds or Arabs.

But what kind of dynamic does the quota system create between Assyrians? This is the most important question. Within the quota system, Assyrians only compete with each other. This is crucial to realise, since it sets the foundation for all of the painfully crude and divisive rhetoric from all of our (“our” used very loosely) political parties when confronted with each other’s agenda. For Assyrians, the only political opponents are other Assyrians, not non-Assyrians who enact the actual policies that affect us. Assyrians only need to challenge other Assyrians; undermine other Assyrians; and object to other Assyrians. At no point do they need to confront the real victimisers and oppressors on an election platform.

What good is the quota system if it doesn’t even serve its own specific purpose of safeguarding the voice and representation of minorities when more than half of the list running in the election are KDP-creations and affiliates? What good is it when even Arabs have their own proxy with no connection to the Assyrian people? As time has wore on in Iraq, this quota system has been repeatedly abused by non-Assyrians who have the resources to abuse it. And all for a pitiful 5 seats. This is not even factoring how clergy have just as many if not more meetings with local and international politicians than our elected representatives do.

Moreover, the quota system concedes both that we are not part of mainstream society and that mainstream society is not fit enough to accommodate us or our demands. And there is truth to it. Our ethnic identity is still not given indigenous status; our language is not enshrined in the Iraqi constitution as an official language alongside Arabic and Kurdish; our genocides, including Simele, are not recognised; and our towns lie in ruins, being fought over by the more equal Arabs and Kurds. What the quota system seeks to provide is an avenue to address these failures and prejudices, but it cannot. I contend that 5/329 seats in any parliament, much less one characterised by obscene levels of corruption, is not the defining element of our degradation as a people and our offensively minute position in Iraqi society. Even if all 5 seats were occupied by one party with one vision, I honestly do not think there would be radical change on the ground. In any case, 5 people in parliament do not have influence in matters outside of their small constituency — that responsibility is on people themselves.

And people don’t care about seats, they care about security, heating, electricity, employment, and education. These are the things politicians in Iraq sacrifice at the altar of their own unchecked greed. In a country where 99% of all government revenue is generated by the oil sector, only 1% of Iraqis work in the oil sector. Where most governments rely on meticulous paper-trails and the taxation of private individuals and companies to support public spending projects— the Iraqi government directly creates its own source of revenue by being the sole owners and administrators of Iraq’s oil industry. Thus, corruption will not be addressed in Iraq until its economy is diversified away from government monopoly. It is important for Assyrians to digest that in the context of what our potential representatives promise and what they can feasibly deliver.

The upcoming elections are nevertheless important for Assyrians for three reasons.

- We should not concede to the superior resources of Kurdish parties and their handful of Assyrian accomplices which seek to divide and distribute our lands between them. These lands belong to our mothers and fathers and to our sons and daughters, not a violent mafia engaged in a turf war. We must identify the policies we need and support those who advocate for them.

- If we abandon the political process owing to growing apathy and hopelessness, we also abandon the Assyrians who still must believe in it given the overwhelming weight of arms and violence against them. We must not leave our fate in the hands of others, and we must contribute to our own protection according to our needs and agenda. The only way a robust case for this can be made is if individuals are given a mandate in a representative democracy and held accountable for their actions. There are successes we can identify too and back those responsible for them— we should not think absolutely everything has been a failure.

- Lastly and most importantly, Assyrians need to ensure the NPU have a political channel in Baghdad’s parliament. It is unclear what their fate would be if the worst possible scenario should occur: the ADM loses both it’s current seats. In this case, the NPU may very well stop receiving support from the Federal Government. If this should happen, the lives of ordinary Assyrians would be entirely in the hands of Kurdish peshmerga and Arab soldiers— groups who have already demonstrated their primary interests are their own, not ours.

Considering the above, the ADM must be supported as Assyrians seek to rebuild Nineveh. It has consistently objected to the annexation of the Nineveh Plain to the Kurdistan Region; it objected to the referendum being administered in the Nineveh Plain (the only areas which were not forced to participate were areas secured by the NPU); it helped stand up the only recognised fighting force of Assyrians in Iraq as an urgent response to ISIS; and finally they commanded enough authority to pass a province solution in parliament in 2014. They have done this in the face of incredible challenges we underestimate or submerge in our cynicism. But lets look at reality: the NPU is a real thing Assyrians feel a real benefit from. It is our only bit of leverage and agency in a country which has largely deprived of us any— and we must not surrender it.